About Us

OUR AIMS

The Eckersley Shakespeare Trust is a registered charity,

UK Charity Number 1083174.

Established in 2000 with the general aims to:

1. Advance the education of the public by promoting the study of the life and works of Shakespeare and his contemporaries...

2. Carry out research into the life and works of Shakespeare and his contemporaries and to disseminate the useful results thereof for the benefit of the public.

OUR MISSION

Within the context of our charitable aims we wish specifically to promote: the research, study, amplification and development of the Shakespearian studies contained and arising out of the works of the late Sylvia Eckersley and to make these available to the public and for the benefit of all.

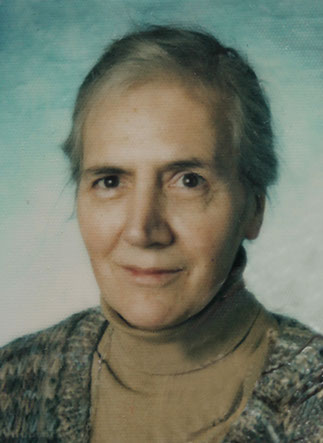

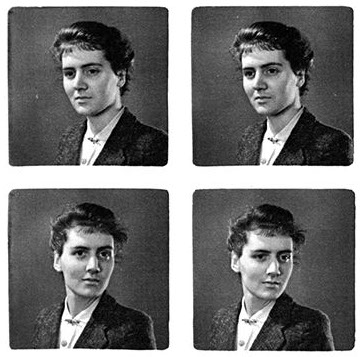

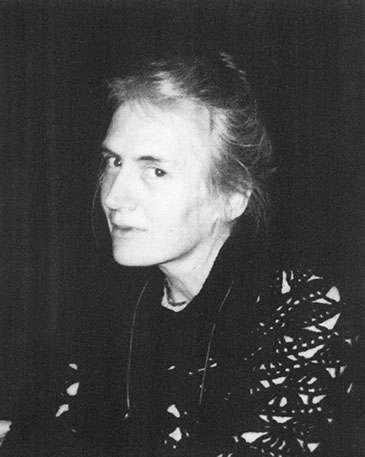

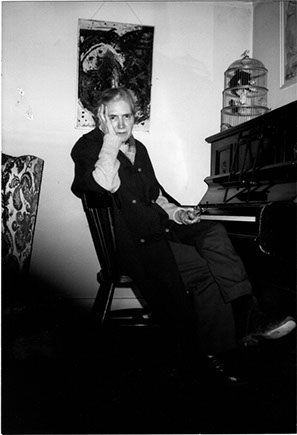

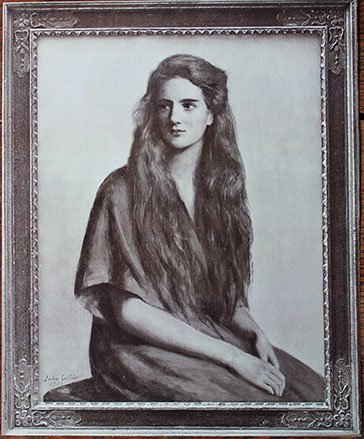

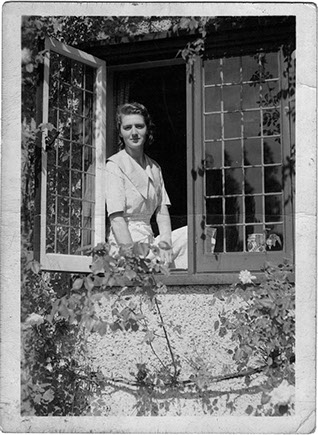

SYLVIA ECKERSLEY

Sylvia was born in Danbury, Essex, as the second of three children. Her mother was a pianist, composer, and music teacher, and her father was an eminent physicist. Sylvia had a happy childhood, climbing trees and playing tennis, and would often make lightning sketches of people and animals. She was obviously very gifted and attended a private boarding school at Runton Hill, where she excelled as a pupil. However, at the age of eighteen, the onset of rheumatoid arthritis became apparent, and this was to plague her for the rest of her life.

After leaving school she studied, in turn, architecture, journalism, and medicine, spanning in total a period of eight or nine years. However, for various reasons, including ill health, her professional studies were always cut short. She used to say she was the best-educated undergraduate alive! Despite increasingly severe physical deformities, the miracle was that she never completely lost her physical mobility and was able to live semi-independently almost until the time of her death.

In her late 20s, Sylvia made a strong connection to the founders of the Camphill Movement in Aberdeen, Scotland. The philosophical principles inspiring this movement, dedicated to social renewal and the impulse for life sharing together with individuals having developmental difficulties, opened for Sylvia deep questions around the theme of human destiny and the unfolding of the human spirit. The underlying writings of Rudolf Steiner and Karl König became immensely important. Sylvia stayed in Aberdeen for the best part of a year and became, for several months, Dr. Karl König’s private secretary. However, her health was not strong enough to sustain the rigors of Camphill life in the long run, so she left to become a teacher, initially at Michael Hall School in Sussex. She made many strong connections at this time, especially with Francis Edmunds, the founder of Emerson College, Cecil Harwood, and Owen Barfield, who was part of the ‘Inklings circle.’ together with C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. The friendship with Cecil Harwood was to have a particularly deep influence on her for many years.

‘If we imagine a Shakespeare play as a deep pool, the play which we are familiar with can be likened to the images which play on the surface of the pool. They have great richness. Yet, of a sudden, one’s gaze can start to see through the surface into the life within the pool’s depths’.

Sylvia loved teaching but found it exhausting. In order to cope with this, she did not take on any permanent post but became peripatetic Waldorf School teacher, traveling around the British Isles, deputizing where necessary and doing upper school teaching in virtually any subject – she was equally gifted in mathematics as she was in languages, English literature, history, and geography. Two schools to which she made particularly strong connections were the Edinburgh Rudolf Steiner School and Michael House School in Ilkeston. She also worked for a time as a journalist in London.

Around 1960 her life changed direction somewhat. She moved to Cornwall and became friendly with the artists’ group in Mevagissey, earning some money through translation work. She took up residence in Heligan Mill, a remote house in the middle of a forest near a place that has since become known as the ‘Lost Gardens of Heligan’. Part of her task there was to look after her friend’s growing son, but this still left her with a lot of time on her hands. She took to coaching a young man for his school exams – and the work he was studying was “The Merchant of Venice.”

And thus began what was to become a life-long interest in the works of Shakespeare. She soon found that the whole play was actually symmetrical, only realizing later that others had previously discovered this fact. “That other scholars had noted scene symmetry, at least sometimes, in Shakespeare was fascinating, but what they didn’t seem to have noted was the extraordinary stanzaic structure of the first scene.”

This led Sylvia to a detailed study of the structure of “The Merchant of Venice,” which she described as “looking down through the surface of the sea to the depths, with everything suddenly taking on a new character and meaning.” This experience proved to be the first step in a process of investigation, which, as time went on, became the dominant motif of her life.

After fifteen or so years, she left Heligan and moved to the New Forest, near Salisbury, establishing a connection to a group of actors who were interested in her ideas on Shakespeare. She initially lived in lodgings and later, when her mother died, in her own bungalow in Milford Hill, Salisbury, to which she moved in 1979. This was to remain her home until she left, in 1999, for Stourbridge.

A particularly important period, a new and decisive turn, in connection with Sylvia’s Shakespeare studies were while she was working as a teacher in Michael House Rudolf Steiner School, in Ilkeston, preparing a class for a performance of ‘Macbeth.’

In order to produce the play, she felt that she would need to learn the whole text by heart, no small challenge for anyone, but a necessity for Sylvia, so she thought if she was to be able to manage the class and the production, given her increasing physical limitations.

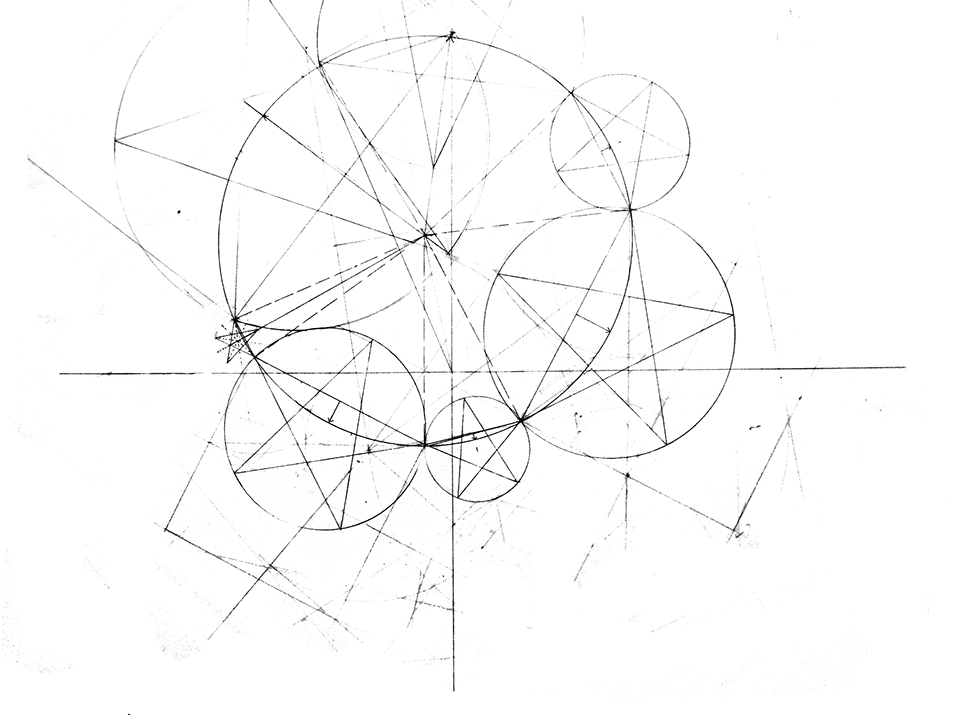

It was through fulfilling this mammoth commitment and then, shortly afterward, discovering the First Folio edition of Shakespeare’s works, which she, like many other scholars, had previously dismissed as unreliable, that it began to become evident to her that there was not only scene symmetry and possibly play symmetry but also act symmetry in Shakespeare’s plays.

The realization of this marked a real threshold because so many critics were of the opinion that acts were arbitrary inventions and did not really mean anything. The question that arose was: how is this possible? How can three kinds of symmetry co-exist, intermingled but also somehow working together in harmonious synchronicity?

Sylvia’s pursuing of this question and its remarkable outcome is a saga in itself and unfolded at length in her book, ‘Number and Geometry in Shakespeare’s Macbeth.’ (Floris Books, 2007). Suffice it to say that she broke through to what many have considered to be revolutionary insights with potentially significant implications, both for understanding the content of Shakespeare’s work and for its dramatic production.

Sylvia died on Palm Sunday 8th April 2001. Only two years previously, there had been good reason to fear that the fruits of Sylvia’s lifetime of research and writings on Shakespeare would be lost with her death.

However, it has proved possible to salvage Sylvia’s work and literary legacy in the nick of time. The devoted work of several colleagues led to the potential for an archive to be created – and with the dedicated help of Alan Thewless during the period 1999 to 2001 Sylvia’s book on “Macbeth” was substantially completed before her first stroke. It was also possible, particularly with the help of the late Dr. Vivien Law (Reader in the History of Linguistic Thought at Cambridge University and Fellow of Trinity College) and Professor Robert Nigel Alexander (Glasgow Academy, St Andrew’s University, Magdalen College Oxford) who wrote academic references affirming the validity of this research and its general educational relevance, to establish the ‘Eckersley Shakespeare Trust’ to administer her literary legacy. Confirmation of the registration of this Trust was received on the very day that Sylvia was admitted to hospital following her first minor stroke, after which she did not return home. The synchronicity of her life, particularly in the later years when she made several courageous life-changes to facilitate the availability of her work and the publication of her book seemed almost to match the symmetry and synchronicity that she had herself discovered in Shakespeare’s writings. A treasure trove of valuable notes and geometrical calculations are now to be found in her literary archives (Archives of the Eckersley Shakespeare Trust), which are gradually being made more available and asking for careful study and further elaboration.